- Home

- Critical Decade

- HI Climate Action

- HI Commission

- HI Resources

- HI Equity

- HI Events

Uncloaking the Cost of Carbon: Applications in Hawai’i

As the state’s Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission ponders its many mandates to coordinate action in Hawai’i, it is looking with interest at how to incorporate damages from greenhouse gases into public projects. There are many measures that the State of Hawai’i might adopt to reduce the future damages and risks of climate change. Some might be inexpensive or even pay for themselves; others might be rather costly. From an economic perspective, it would make sense to start with the inexpensive remedies before proceeding to more expensive ones.

As the state’s Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission ponders its many mandates to coordinate action in Hawai’i, it is looking with interest at how to incorporate damages from greenhouse gases into public projects. There are many measures that the State of Hawai’i might adopt to reduce the future damages and risks of climate change. Some might be inexpensive or even pay for themselves; others might be rather costly. From an economic perspective, it would make sense to start with the inexpensive remedies before proceeding to more expensive ones.

But how expensive is too expensive? Using the social cost of carbon (SCC) can be helpful in answering that question. The social cost of carbon is an estimate of the damages that putting an extra ton of carbon into the atmosphere will do, recognizing that most of that ton will stay aloft for a long time, but some will be absorbed into the ocean and terrestrial ecosystems as well. It’s a useful benchmark because it allows decision makers to understand if the preventative measures they are proposing are worth the money, or if they are being cancelled out by other “carbon expensive” projects. It wouldn’t make much sense for people to spend a lot more money to keep a ton of carbon out of the air than it would cost in damages if that ton were put in; nor would it be economical to spend a lot more on adaptation measures than the cost of the damages that might be prevented. The SCC is an indicator of how much it’s worthwhile to spend in order to prevent climate change damages.

Putting a Price on Carbon. Coming up with an estimate of the SCC is not easy. First of all, the damages from climate change are multifaceted and often feed off each other: damage to coastline infrastructure and public beaches from rising seas and more frequent hurricanes; increased flooding and erosion from more intense rainstorms; rising costs of healthcare and illness; agricultural impacts; reduced revenues and profits from tourism; drops in commercial and recreational fishing; and so on. Secondly, damages don’t occur all at once-They are spread out and persist over years into an uncertain future. This means researchers must decide on how to weigh future damages against near-term damages. Thirdly, there are important costs that are difficult to put into monetary terms, such as losses of Hawaii’s exceptional but threatened biodiversity, threats to cultural and spiritual practices, and threats to human life.

Hanalei during the 2018 Kaua’i Flood. Photo courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard video by Petty Officer 3rd Class Brandon Verdura/Released

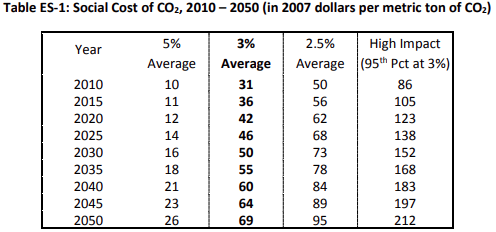

Scientists and economists together have attempted to estimate a range of plausible values, using the best research studies available. The table below shows a range of estimates those efforts have produced. Clearly, an important factor is the extent to which damages happening in the future are discounted relative to those happening soon, since climate change is long-lasting and probably permanent. How much future damages are discounted is a value judgment and should be influenced by the realization that those future damages will be our bequest to our children and grandchildren, and might turn out to be much worse than we now realize.

Using the lowest discount rate (2.5%/year), which still values damages in 2050 only about half as much as damages in 2020, it would be worthwhile to spend at least $62 to keep a ton of CO2 out of the air and as much as $123 in a worst-case scenario. More recent estimates are even higher. A United Nations report estimated that carbon taxes (read, SCC) should be set at $135 to $5,500 per ton of CO2 by 2030 to prevent a 1.5 degree Celsius global temperature increase. Fortunately, Hawaiʻi has many mitigation options that would cost much less than that.

The Need for Team-players. These numbers highlight another important issue. Obviously, since carbon dioxide is a global pollutant that changes the climate- not just in Hawaiʻi- but in countries all over the world, the total global SCC is much higher than the cost to Hawai’i alone.

Should policymakers in the State focus only on the costs of Hawaii’s CO2 emissions on Hawaiʻi and ignore the effects of their decisions on other regions? Clearly, if all states and nations took this approach, the world would experience a disastrous “tragedy of the commons” and all would suffer the consequences of lack of cooperation. The actions they would take in their narrow self-interest would collectively fall far short of those necessary to prevent extreme global warming. Solutions to the climate problem demand that policymakers recognize their mutual inter-dependence and act cooperatively. Mitigation measures should be judged against the global SCC.

Wildfire on Mau’i, 2019. PC: Department of Land and Natural Resources

The SCC also provides some guidance to help resolve the difficult question of how high to set a potential tax or fee on carbon dioxide emissions. Hawaii’s state senate passed a carbon tax measure in the 2020 session, and some measures have already been proposed for the current session. If the tax rate were equal to the SCC, then all energy uses would reflect their true cost. It’s worth noting that these calculations of the SCC are well below the estimated tax rate needed to hold temperature increases below the range of 1.5-2.0 degrees centigrade- the range that international conferences have adopted as a target aimed at avoiding the most serious consequences of global warming.

So, the SCC, despite its uncertainties, is useful for guiding public policymakers in Hawaiʻi. As the State’s Commission delves deeper into this tool, it would do well to work on a national scale with the US Climate Alliance and the reestablished Interagency Working Group by the current federal administration to realize the full cost of mitigation projects and correct the balance as to where public funds are spent by uncloaking the cost of carbon.

Author Bio:

Dr. Repetto, now retired, is an economist (Ph.D., Harvard University) who has worked on natural resource economics, environmental economics, international development, and climate change issues for a long time. He has worked at many institutions such as WRI, Pew Charitable Trusts, Ford Foundation, IISD, and the UN Foundation, and taught at Yale University. He pioneered the inclusion of natural resources in national income accounting, and worked with several national governments to incorporate these into their national income accounts (Wasting Assets: Natural Resources in the National income Accounts; Accounts Overdue: Natural Resource Depreciation in Costa Rica, and others). Dr. Repetto is also the author of several books, publications and articles, including America’s Climate Problem: The Way Forward and is a guest contributor to the Hawai’i Climate Blog.

Disclaimer: The views and positions expressed on HIBlog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and positions of the Hawai‘i Climate Commission or the State of Hawai‘i. If you notice an error in our research or have concerns about quality, please contact Anukriti Hittle at [email protected].