- Home

- Critical Decade

- HI Climate Action

- HI Commission

- HI Resources

- HI Equity

- HI Events

Clean, Equitable, and Resilient: Does Telework Check All the Boxes? (Hint: It Doesn’t)

2020 has been a year that many may liken to a dystopian novel, though instead of labeling workers as “alphas” “betas” “gammas” or “epsilons”, we have been deemed essential or unessential. While some might view essential workers as the lucky ones, the sacrifices made by them as they continue to work in highly social jobs in the midst of a pandemic are often overlooked. As the non-essential workforce is waking up shortly before its work day starts, shimmying on a professional top over pajama bottoms and preparing for the morning commute from coffee pot to home office, a large portion of the state’s work force continues to commute to offices, restaurants, and stores to start the work day in person. The inequity in essential versus non-essential workers’ situations is clear.

2020 has been a year that many may liken to a dystopian novel, though instead of labeling workers as “alphas” “betas” “gammas” or “epsilons”, we have been deemed essential or unessential. While some might view essential workers as the lucky ones, the sacrifices made by them as they continue to work in highly social jobs in the midst of a pandemic are often overlooked. As the non-essential workforce is waking up shortly before its work day starts, shimmying on a professional top over pajama bottoms and preparing for the morning commute from coffee pot to home office, a large portion of the state’s work force continues to commute to offices, restaurants, and stores to start the work day in person. The inequity in essential versus non-essential workers’ situations is clear.

The return of cars on Hawaii’s highways. In the first few months of the pandemic driving down the H1 was a dream, and though grocery stores were often lacking toilet paper, finding a parking spot was hardly ever an issue. Climate enthusiasts were vocal about the positive impact COVID-19 restrictions would have on our environment, citing decreases in Greenhouse Gas emissions and evidence that “nature was healing” as the world saw ecosystems flourish amidst the short-lived anthropause. As Hawai‘i has begun to climb the tiers set forth by Governor Ige’s Covid-19 Framework, more designated businesses and operations have opened their doors for business once again. The state has seen an increase in tourists and employment, and along with those, traffic and emissions. A recent study by Streetlight “COVID Transportation Trends: What You Need to Know About the New Normal” (2020), shows that Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) is trending back to pre-COVID levels for various reasons, including that essential workers are just that—essential and must travel/commute.

Telework: One piece of the emissions puzzle. As Hawai’i prepares to become “climate ready”, the state continues to look for pathways to reduce emissions from the transportation sector, while also being equitable and resilient. Telework may be part of the solution to reducing single-occupancy vehicles and vehicle miles travelled (VMT), but it cannot be considered on its own as it is not clear that teleworking is the “cleanest” answer. Studies show that the correlation between telework and reductions in emissions and VMT are not straightforward; the Victoria Transport Policy Institute demonstrated that the original decrease in emissions/VMT from telework are often met with a rebounding effect. These effects are natural outcomes born from opportunities telework provides, such as urban sprawl and increased VMT for errands. Teleworkers also may make additional vehicle trips to run errands that would have otherwise been made during a commute, or use their cars to leave their home offices for breaks.

Telework: Only somewhat resilient… The COVID-19 pandemic was not the first time the country has seen a sudden shift towards teleworking. After 9/11, and ensuing anthrax attacks, several government offices were required to close. In 2004, Congressman Tom Davis announced that “We now realize that telework needs to be an essential component of any continuity of operations plan. Something we once considered advantageous and beneficial has evolved into a cornerstone of emergency preparedness.” For 16 years, states have recognized the need to enhance telework opportunities and develop telework plans, yet when pandemic closures first hit Hawai‘i, the state was not prepared to telework as state agencies looked for guidance from a 10-year-old Department of Human Resources Development document. It contained neither the new pandemic realities, nor was quickly implementable and so, not resilient. As the frequency and intensity of natural disasters increase in the face of climate change, how will telework hold up in the event of a power outage caused by a hurricane?

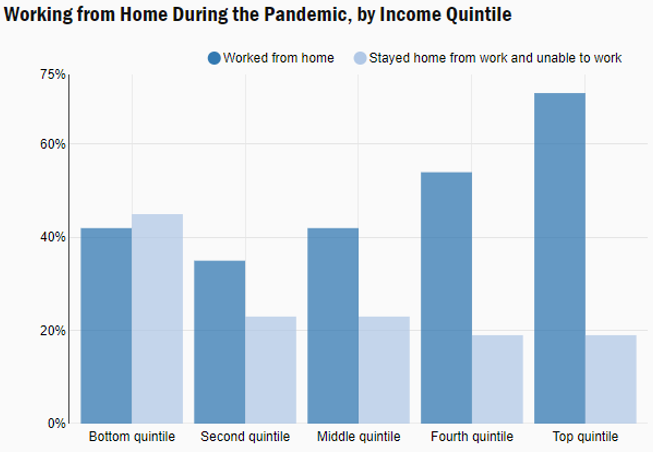

…And not equitable. Telework scores less impressively in equity. Focusing solely on a shift to telework disregards the large portion of the state’s workers who are low-wage, young, working in a vulnerable occupation, or a combination of all risk factors who simply do not have the option to work from home. An analysis by the Department of Business, Economic Development, and Tourism (DBEDT) identified sales, food preparation and serving, transportation and material moving, personal care and services, education training, library, and arts, design, media and entertainment as the most economically vulnerable occupations in Hawai‘i. These occupations make up 40% of the state’s work force, and are considered vulnerable because of their heavy reliance on tourism, as well as their in-person requirements. Low-wage workers and young workers, which are also at-risk populations according to DBEDT analysis, make up more than half of the employees in vulnerable occupations. A study by the Brookings Institution confirms that teleworking is far more common among higher-paid professionals.

Teleworking can also have a disparate impact on disadvantaged groups, such as women and racial minorities. It requires access to highspeed Wi-Fi, a necessity that is far less common in areas with lower median incomes and rates of education, more residents of color, and with smaller rural populations. It also requires a home environment that supports productivity. With COVID-19 shutting down schools, childcare, and other household services, many women end up carrying a heavier burden of childcare and domestic chores, making it difficult to telework. Women are also disproportionally concentrated in the most vulnerable occupation sectors mentioned above.

Telework must be supported by multimodal commute strategies—to address emissions and equity.

Post-pandemic, while encouraging a shift to telework will no doubt provide positives for many workers and employers in Hawai’i, it is important that we spread the commuting benefits across the board. Besides, more incentives for essential workers to utilize climate-smart commute strategies would surely aid the state’s mission to reduce VMT and emissions. Examples of programs that address equity in reducing emissions from commuting and transportation are seen in Seattle, Washington State, Chicago, and Washington DC. These programs support equitable pathways to reducing VMTs and emissions by facilitating access to public transport through monetary incentives, flexible schedules, and special programs- such as a guaranteed free rides home for carpoolers when they miss their regular ride. Seattle’s “Commute Trip Reduction Program” has brought the state a decrease in commuters driving alone, with over 66% of employees of participating businesses opting for commuting by transit, bike, walking, or carpooling. And even with governments working towards clean and equitable transportation programs, groups like the Coalition for Smarter Growth are ensuring the benefits are spread across the board. Washington DC’s “Transportation Benefits Bill” originally incentivized employers to provide employees with a subsidy benefit for driving and parking. The Coalition for Smarter Growth recognized that most DC residents don’t drive to work- 18% walk or bike, and 37% take transit. With this knowledge, they worked to push through the “Transportation Benefits Equity Amendment”, which made subsidies available to those who take transit or bike to work as well.

Putting frontline workers first: equity in transportation. Although a modern telework policy is needed for the state, telework cannot be considered in isolation—neither for emissions reduction, resilience nor equity. Coupling telework programs with strong multimodal commute options would ensure that marginalized workers who often do not have the option to telework can still benefit from a shift towards a cleaner state. Providing essential workers with access to affordable transit and incentives for climate-smart commuting strategies will enable the state to be truly equitable and resilient in reducing transportation emissions. COVID-19 has made apparent how the seemingly mundane interactions make our day-to-day lives more enjoyable—that perhaps these are the basic building blocks of our society and our lives. Trips to grocery stores, chats with your favorite barista, and stumbling upon live music at a local restaurant are all made possible by workers in the most vulnerable occupation groups. To leave no worker behind, we need to make right the situation for our most essential workers, and put them where they belong—first.

Disclaimer: The views and positions expressed on HIBlog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and positions of the Hawai‘i Climate Commission or the State of Hawai‘i. If you notice an error in our research or have concerns about quality, please contact Anukriti Hittle at [email protected]